When it comes to the forging of purpose and identity, it’s hard to know how much, if any, is up to you and how much, if any, is up to God. This is a classic vocational tension that Christians have been wrestling with, like, forever.

But what is most difficult is when you try to step into a life as you sense God calling, and it just doesn’t work out how you thought it was supposed to. God doesn’t seem to uphold his end of the deal, so to speak.

I just recently moved to Salt Lake City, UT to start a flight training program. The goal is to become a commercial airline pilot. Needless to say, given what I thought I’d be doing with my life, this new trajectory is a bit of a non-sequitur, and it still feels slightly absurd. When I initially told my pastor back in Spokane that I was considering this path, he laughed at me.

In the big picture, however, it really isn’t so absurd. But I have struggled to tell the story to myself, and even more so to others, about “why I’m doing it” because this new path was born out of a much deeper, convoluted, spiritual story that is just now just coming into focus. It’s a story that really has nothing to do with becoming a pilot, but at the same time, has everything to do with becoming a pilot.

I wanted to try and get some of this story written down, because it really is a story about God’s work in my life, a kind of resolution or climax to events several years in the making. It’s often all too easy for me to keep my happy experiences to myself to the benefit of nobody. But I was feeling compelled to write this out, because ultimately it’s a kind of testimony. And testimony–the act bearing witness to God’s work in your life or in the world–is like, the Christian’s ONE JOB.

In addition to that, I think it’ll have a lot in common with those of you who have 1) recently-ish graduated 2) love Jesus 3) have deep hopes for the restoration of the world and for your small role within in it, and/or 4) feel relatively disillusioned or lost or disappointed or sad and feel like you’ve just been treading treading water and wasting time and being a cynical, apathetic lump of dirt in the face of the world’s great need, and lo, even in the face of the world’s tiniest and humblest needs, and holy shit, what gives anyway, like, what’s my problem, and what am I supposed to do in the space of yet another vacuous, absurd, spiritually void day in which I seem to be both the perpetrator and the victim of my own spiritual apathy?

So without further ado:

THE SHORT VERSION OF HOW JONATHAN STRAIN DECIDED TO BECOME A PILOT

One day in the late fall of 2016, I was on a hike with my Aunt Cindy in Colorado. This was right after all the things I thought I’d be doing with my life had all finally keeled over and died. Aunt Cindy, God’s most dedicated vocational cheerleader, threw out a question somewhere along the lines of, “What’s something you’ve always wanted to try but haven’t, career path or not?”

This was the first time I had told someone out loud, “Well, I’ve always wanted to learn how to fly a plane.”

It was another year and a lot more details in between before this actually became a real plan, but anyway, that’s the short version.

AND SO, BUT OK, THE LONGER VERSION OF HOW JONATHAN STRAIN DECIDED TO BECOME A PILOT

No matter what path you take, I don’t think there’s much escape from your first year or two out of college being an experience of pallid disillusionment in some degree or another. This is for a lot of reasons: loss of friendship, extreme novelty (new job, new home, new city), adjusting to the reality of everyday lived-life after all the “change-the-world” pomp you’ve been blasted with during your years in college, especially if you attended a progressive Christian university.

My first year out of college was no exception. I spent my first year out of school as an AmeriCorps volunteer with the Jesuit Volunteer Corps Northwest. This year is a story in itself, but to put it succinctly, it was an intensely internal, spiritually vacuous, soul-stretching year. For a multitude of reasons, I did not ever feel at home during my time with JVCNW.

Don’t misunderstand, though. I am deeply thankful for this year, for my fellow JVs I served with, and for the community that gave us a home there. I do believe that deep work was happening beneath the surface of my being, like a tree sinking its roots deep down. But as far as the experience itself went, there was little fruit produced by that tree in that year. It was a year full of questions.

The early 20th century poet Rainer Maria Rilke was my thematic companion, and his words in the collection Letters to a Young Poet became something of a spiritual bedrock for me. He writes:

“You are so young, so before all beginning, and I want to beg you, as much as I can, dear sir, to be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and to try to love the questions themselves like locked rooms and like books that are written in a very foreign tongue. Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer.”¹

One thing that helped me finish out the year with JVCNW was that I started seeing a counselor, and part of what she helped me do was give me allow me to begin thinking in anticipation of the future. She allowed me the space that I wasn’t giving to myself to look forward to life after my service year instead of feeling guilty. Quite a simple concept, but it had a profound impact, and would prove to be a concept I’d have to return to later down the road. In this context, this meant anticipation for reconnecting with my friends and community back in Spokane, a place where I felt known and loved.

I saw my impending return to Spokane as an opportunity to step more fully into the values that drew me to JVCNW (community, simple living, social justice, spirituality), but in a setting that was less inherently temporary. I had learned to see all the problems of the world as being an interconnected web, and that the most direct way to begin to address systemic brokenness was to align my own life into a new system of living. When it came to issues like national health crises, climate change, generational poverty, the breakdown of families, income inequality, overconsumption of fossil fuels, global hunger, and the list goes on and on–the basic gist is that I came to believe that the simplest and most profound way to help the hurting world was to begin by helping your hurting neighbor, and maybe planting a garden on the side.

I wanted to be more holistically involved in my Spokane church, which was and still is dreaming about being neighborhood-centric in its missional scope. I believed, firmly, in the necessity of the social Gospel, that the Church is not limited to facilitating personal salvation experiences for nice, middle class, white people, but that Jesus calls us outward into a systemically broken world: poverty, racism, sexism, homelessness, whole populations of people getting the short end of the cultural stick in ways that were not only being ignored by the American church, but often even perpetuated.

In the model of Jesus, I aspired to a lifestyle of downward mobility. I wanted to intentionally abdicate the power my culture affords me, to live below my means, to be a servant. I saw this not as the righteous path of the privileged white liberal with a guilt-ridden savior complex, but as the authentic call of my own faith journey, a moving outward from the work Jesus had done in my own life. It was one of those I-don’t-actually-know-how-to-do-this-but-I-trust-that-Jesus-will-show-me types of calls. This is important to note, because in spite of all that would happen later, I still sense the authentic reality of this call in my life with the same degree of importance.

But now, I also have an abiding peace and freedom sourced from the well of kairos, the deep well of God’s time which has its fullness in every moment. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

In my return to Spokane, I envisioned a life of creative simplicity, routine, and purpose, all in the scope of greater Christian community. I wanted to learn how to keep bees (or something), build my own stuff, mentor at-risk youth, and to write. Employment, as a way to make a living, would simply enable me to engage in these pursuits. The pursuit of future schooling or vocational training, I hoped, would flow out of this vision, rather than the other way around. All of this was rooted in my earnest and informed desires to be in close connection to God’s earth as producer and consumer, to be more rooted in a particular place with particular people in community, and for all these endeavors to be a grand labor on behalf of and because of the Kingdom of God as I grew to understand it, love it, and hope for it. Essentially, I wanted to be a modern monastic, a Super Monk!

Unfortunately, Super Monk began to die almost as soon as he took his vows.

Back in Spokane, I hit the ground running. I got a job at a coffee shop, and started volunteering as a high school leader with a youth ministry in Spokane called Youth For Christ (YFC) which was rooted in serving kids in one of Spokane’s more low-income and racially diverse neighborhoods. As an added bonus, my dear friends Jon and Emily Royal were also working at YFC as full time staff. I reconnected with my church, which later even moved into that same neighborhood to share YFC’s building. I moved into a house of guys I knew from Whitworth, and even impulse-bought a drill for all the DIY projects I was sure to begin working on–building my own furniture and garden beds and all that. Life held the possibility of Super Monk’s ecstatic vision.

But as I began to walk through actual lived life, the vision started to fall flat. My sense of connection and care paled in comparison to the grand, though admittedly oblique, vision of Super Monk, and the realities of daily existence began setting in. I wasn’t working nearly enough hours, and was anxious about money. I was not experiencing or acting upon the grand connection to community I had envisioned. I felt disconnected from my housemates for what seemed like no reason at all. I slept in a lot, worked my 15-20 hours a week as a barista, drank beer, and forced myself to keep showing up at YFC, a place where I certainly felt a deep sense of spiritual vitality–the work of the Holy Spirit moving–but not in my own connection to it.

Part of my hope for becoming a YFC leader was to invest in longer-term mentoring relationships (even just 1 or 2) with kids in the neighborhood. But at this prospect, I balked. Every once in a while, I did have moments of connection with students that were life-giving, joyful, and natural. But on the whole, when it came down to the routine discipline of connecting with students, I just didn’t want to do it. And who would want to be mentored by someone who is acting more out of abstract obligation and idealism, rather than because of you? I struggled with this though, because oftentimes our heart really does follow our actions. I desperately wanted to want to do it, and assumed it was well within God’s power to give me that willingness if he saw fit. Sometimes we have to step into the unknown thing and trust that God will provide us with what we need, and this ministry was a significant part of what I felt called to in this season of my life. And YFC, like any Christian youth ministry, was always hungry for qualified volunteers.

But in a context like YFC, where many of the youth have been hurt by a lack of follow-through from the adult figures in their lives, you can actually cause more harm than good through a flabby commitment. I continued to waver on this prospect of mentoring, and kept myself from really diving in.

When it came down to doing all the things I had envisioned myself doing, I simply would not and could not do them. I found myself relating much to the old doctor that Father Zosima speaks of in The Brothers Karamazov. “‘I love mankind,’ he [the doctor] said, ‘but am amazed at myself: the more I love mankind in general, the less I love people in particular, that is, individually, as separate persons…I become the enemy of people the moment they touch me,’ he said.”²

I, too, seemed to be experiencing this inverse ratio between love for people in the abstract and love for individuals in real time, becoming more stubbornly resolute in my abstract vision even as it fizzled in reality. When it came down to putting the vision of Super Monk into action, I just didn’t know where to start, and didn’t care to find out. I felt bogged down, lethargic, desensitized. I kept all these troubles and tensions mostly to myself, and in the stress of this self-imposed isolation, isolated myself further.

But what else was there to do? The ultimate failure, in my mind, was to give up on Super Monk, get some dumb job I didn’t like that paid the bills, and live a comfortable, self-contained life.

I was unable to voice this to myself or others at the time, but I recognize now that my basic posture toward the Super Monk vision had become an over-extension of personal responsibility. I often thought that it seemed all-too-convenient that so many privileged Christians didn’t feel “called” to the difficult work on the cultural margins. In the context of what I perceived to be a largely apathetic and privileged culture, I thought, If I don’t do this important but difficult work, then who will? If I can’t even get myself to live according to these values, how can I even hope that others might too? So I slogged forward.

This kind of posturing, I am convinced now, is not a Gospel posture. But at the same time, it was a way of being that I could not will myself out of, and it needed to be allowed to die. The New Thing does not come until the Old Thing dies. This is at the very heart of Christianity, woven into the death and resurrection of Jesus, the moment in time in which all time is contained. But I’m getting ahead of myself again.

It’s important to note that this is much easier to say from the perspective of New Life I believe I am now writing from in the context of this particular story, a perspective I could not have imagined until it was given to me later. But when I was in the midst of the dying process, all I felt in the moment was how confusing and painful it was. Death hurts.

—–

Naturally, with Super Monk looking all frail and sickly as he was, I started to look at other options for moving forward with my life. My best answer for this, as it is for many bachelor-wielding millennials, was grad school. I didn’t really know what I wanted to study, but knew, vaguely, that I cared about writing, communication, language, and the process of meaning-making. My own grassroots Super Monk lifestyle was failing to take shape, but I still felt called to its vision, and began to envisage a life from an academic vantage: the life of a professor.

An academic career seemed potentially well-suited to my temperament and gifts, and I felt it could be a platform from which to play a key role in the formation of beliefs and behaviors of young people at a critical time in their lives. This, I thought, might be a better use of my gifts, a more natural way to use my abilities as a thinker, analyzer, and observer of the big picture as a way to help others do the same. It seemed more distant and aloof than the more “important” hands-on work of Super Monk, but if I couldn’t be a Super Monk in a direct sense, I wanted to at least be in a position to help others to be. And so I sought the path of the Benevolent Professor. I started to research graduate programs in the discipline of Rhetoric and Composition, around the wintertime of 2014 and into 2015.

But the Benevolent Professor was quickly asked to pause the application process, because in January of 2015, a different opportunity came up literally out of nowhere, one that would prove to be a kind of experiential foreshadowing of the New Life. This opportunity was an invitation to join the staff of Young Life Beyond Malibu as a mountain guide.

Photo from Erika Schultz, fellow Beyond staffer

Photo from Erika Schultz, fellow Beyond staffer

Serving with Beyond Malibu was the most profoundly formative experience I’ve ever had. The opportunity came up out of nowhere, a total curveball. But as I involved myself in the application process, I knew that it was where I needed to be. Additionally, since serving as a Beyond Guide requires you to maintain your involvement in youth ministry, movement forward on this path created an energy and engagement with YFC that I did not have before. I spent the springtime before my 1st summer feeling energized, connected, and vital. It was a breath of fresh air.

The most direct effect Beyond had on me was engendering a sense of spiritual confidence and resilience that I simply did not have before. It is such an unmediated, highly distilled spiritual existence up there, with highs and lows experienced with great intensity. And I had never felt more spiritually alive. I had never felt so capable. The Gospel truths about myself, the world, and God’s work in all of never felt truer.

But it was also a temporary experience. It was certainly real food, like manna in the desert for the Israelites, but it did not necessarily translate outside its own experience right away. Like the manna in the story, it didn’t keep overnight. It seemed to feed me only in its own context and timeline.

Because eventually, in spite of my little spiritual revival as a Beyond guide, the Benevolent Professor caught whatever fatal disease Super Monk had. When it came time to make a move, the energy and spark was not there.

So upon finishing my second summer as a mountain Guide with Beyond, I had decided on trying out one last option: a master of fine arts (MFA) in creative writing in order to pursue writing as some kind of full-time venture. It was the path of the Starving Writer, my last semblance of any kind of plan that made sense given how I understood my gifts in conjunction with what I thought was God’s call on my life.

Anyway, try to guess what happened to the Starving Writer.

It was not too long after that, on that hike with my Aunt Cindy in Colorado, that I said, not unflippantly, “Well, I’ve always wanted to learn how to fly an airplane.”

—–

I don’t exactly know what happened to Super Monk and the gang. I honestly think, if God had wanted to, he could have freed me from that posture of over-responsibility I was chained to without having to kill everybody off like that.

But whatever the case may be, it was exactly in that space of loss, confusion, and mourning that I believe God opened up the possibility for me to understand the New Life. Like the counselor I saw during my year with JVCNW, I sensed God trying to help me understand that I could envision a different path for my future entirely, without guilt or failure.

It’s not like I didn’t understand how or didn’t believe that God could act in spite of my own lived experience. And it’s not as if there weren’t moments of joy, clarity, or purpose along the way. But the big picture I’m trying to paint about the experience I was having throughout these years was that, overall, it just felt mostly like a tiresome, joyless slog through the mud. I didn’t know what to work towards, and any attempts to move my life forward were met with my own sustained indifference and lethargy. Even though I hoped for more than this, I also began to lament that life would never be anything different, Jesus or no. It wasn’t anything so dramatic like despair. Just more of a sad resignation. Weariness. Boredom.

It wasn’t such a leap to step into this unimagined future, when the opportunity arose, because everything that I thought I was supposed to do was dead. So why not just step into something new and enjoy it? It’s not like I had anything else going on.

—–

I can’t claim any kind of long-standing passion for flying airplanes. I had never done it before, and I didn’t grow up around anybody that did. All I can claim is that ever since college, learning how to fly a plane had continuously made it onto various bucket lists (presumably once I became filthy rich from the opulent Super Monk lifestyle), and that whenever I flew commercially, I always chose the window seat near the wing and stared out at what was happening the whole time.

But in the movement forward on this path, I started sensing that same spark of energy that the possibility of being a mountain guide had provoked. As I looked into it more, I found that it was not so absurd that I was drawn to it, and that it synced up intuitively with my temperament and gifts. It was concrete work that I can enjoy and feel proud of, but also a lifestyle that would allow enough margin to invest my creative and emotional energy wherever else God might call me. Over time, with much research and processing with family, mentors, and friends, I decided to take the plunge.

But like I mentioned before, while this is a story about how I decided to become a pilot, it also has almost nothing to do with becoming a pilot. I don’t know how else to say it other than, over the space of this last year, God has been showing me a renewed possibility of life. All the things that I had hoped for in that abstract way died painfully, but on the other side of their death, in the space of the New Life I believe God has given me in this season, they are fully alive, having resurrected into the space of God’s time, the fullness of time.

What I mean is that in this last summer, I finally planted a little garden. I brewed beer with my friend Sagen, like good monks do. I finally made a humble and vulnerable move toward Christian community by joining a small group at church. I finally finished (ok almost) a collection of essays about serving with Beyond that I’ve been working on for friggin forever, and I am proud of the result (to be printed and available probably by the end of April). I continue to wash and reuse Ziploc baggies, because somebody has to save the planet.

Per Rilke’s suggestion, I have done my best to live the questions: Will I live simply? Will I become a writer? Will I work on behalf of the poor and marginalized? Will I be more than a passive, privileged, white dude in the face of the world’s global injustices? Is it possible for me to engage in the important work of the world and enjoy it? Does God care? Is the arc of the universe really bending toward justice, restoration, and joy?

And per God’s grace, I am now seeing that I have begun to live my way into the answers. In the death of the life I was hoping for, even felt called to, I am finding that nothing has been lost or wasted.

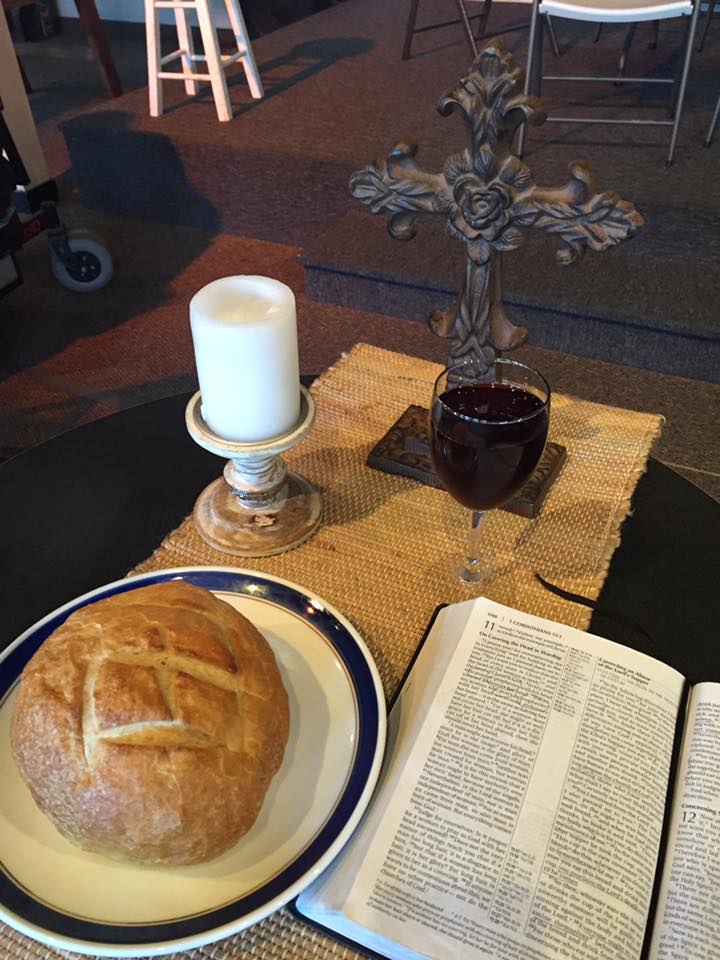

I have no doubt that God will use me as he sees fit, in his timing, according to the work of the Spirit. I mean, I believed that before, too. But now I can actually say, after like four years of relative spiritual drudgery, that God is honoring that faith in real time. But God has also given me the eyes to see that this reality is true for all time. The Bread of Life, Jesus, broken for me, the manna sent down from heaven which sustains our lives both now and forever. Heart of my own heart, whatever befalls, as the hymn goes. The true life that lives on and through and in spite of all our pathetic little gestures, or lack thereof.

I have confidence that my life will undoubtedly be used, and that it already has been and even is now. I have confidence that the path forward is one of freedom and joy rather than of obligation. There is certainly work to do. But because of the freedom of the Gospel, I can act from the knowledge that this call does not rest solely upon my shoulders.

Like, duh. But do you know what I mean?

I sense the resurrected ghosts of Super Monk, the Benevolent Professor, and the Starving Writer all looking down upon me, the spirit of their hopes and dreams not so dead after all.

All that, and I get to fly airplanes.

—–

- Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet, trans. M.D. Herter Norton (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2004), 27.

- Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, trans. Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002), 57.

Photo by

Photo by  Photo by

Photo by  Photo from Erika Schultz, fellow Beyond staffer

Photo from Erika Schultz, fellow Beyond staffer